27 Jul 2025

- 0 Comments

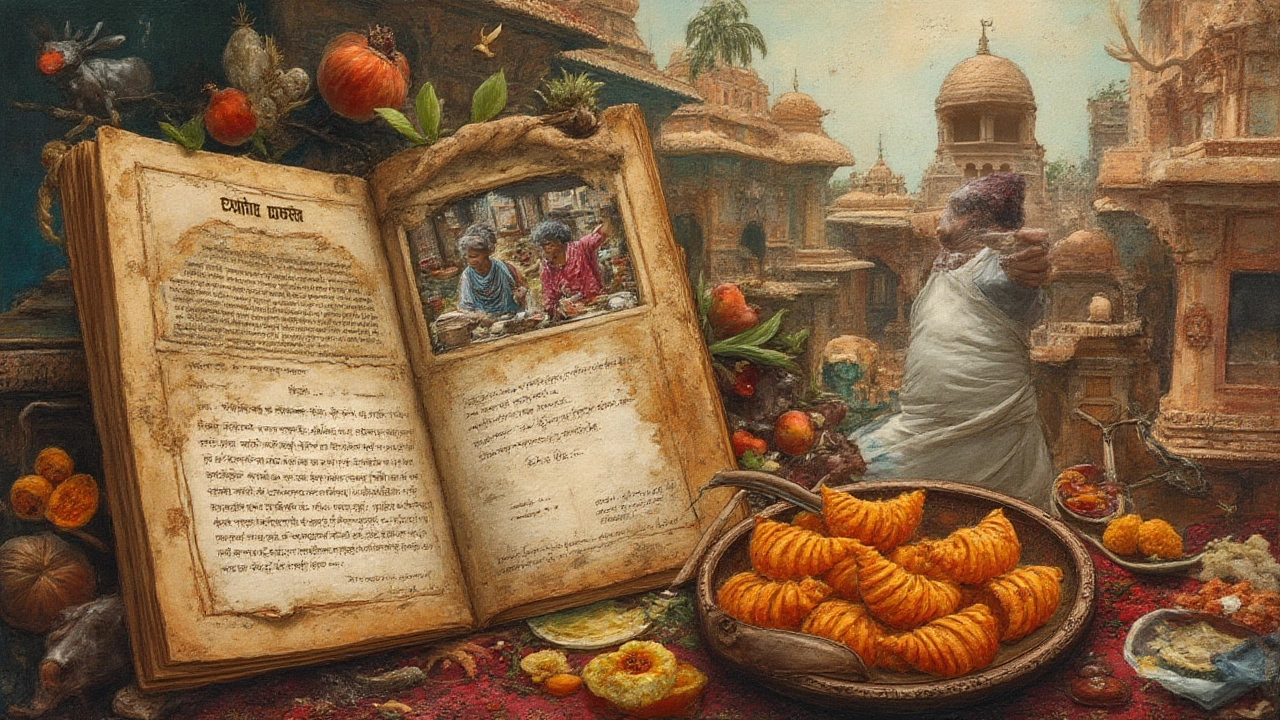

The idea that some foods are forbidden isn’t new, but there’s a reason pork usually stays off the plate in Hindu households. If you’ve ever attended an Indian wedding feast, the odds are high you saw lamb, chicken, maybe fish—and definitely tons of vegetarian dishes. Rarely, if ever, will pork make an appearance. Some might assume this has to do only with religion, others may chalk it up to taste. The truth is more surprising, tangled in thousands of years of tradition, history, health, and even the wild boar’s place in ancient Hindu stories. Ready for a peek under the lid?

The Roots of the Pork Avoidance in Hinduism

So where did this pork problem begin? First, Hinduism is an intricate mix of beliefs, stories, and regional differences. There’s no single text that bans pork outright for all Hindus, unlike how beef is referred to as taboo because of the sacred status of cows. The earliest texts, like the Vedas (compiled around 1500–500 BCE), talk quite a bit about animal sacrifices, including cattle and even wild boars. Back then, society was less vegetarian, and there wasn’t a universal pork ban.

What changed? Over centuries, as Hindu philosophy shaped ideas about ahimsa—that’s non-violence and compassion—the diet reflected these softer values. Cows became strictly protected, and vegetarianism flourished as an ideal. Pork, along with certain other meats, slowly took on a negative reputation, especially as cleanliness and ritual purity gained importance. In some regions like Bengal, pork was once eaten by royals, but such habits faded by medieval times.

There’s another twist—Hindu dietary practices aren’t just about rules from religious books. They’re often shaped by what’s around, what’s safe, and what cultures interact nearby. Islam, for instance, strictly avoids pork. As waves of Muslims settled in the Indian subcontinent, food practices blurred, with pork becoming associated with certain castes (‘untouchables’) or marginalized groups.

One fascinating thing: wild boars actually hold a strange double role in Hindu tradition. On one hand, they’re an avatar (Varaha) of Lord Vishnu who famously rescued the earth in myth. On the flip side, domesticated pigs—seen digging around, often considered unclean—did not get the sacred treatment that cows or peacocks did. Fast-forward to colonial India, and Christian missionaries also discouraged pork among converts, linking it with ‘impurity.’ The taboo became tangled up in more than just old beliefs. It was part health, part group identity, and part politics. To this day, pork is less common across large swathes of India, especially among upper castes and religious Hindus.

Cultural and Social Layers Behind Hindu Pork Avoidance

Let’s talk food and class. In India, food isn’t just about taste; it’s about what it signals. Who you eat with, what you cook, what you buy—it all marks social status. For centuries, pork was branded a ‘lower-caste’ meat. Pigs were scavengers, roaming dusty streets, cleaning up food waste. Many upper-caste Hindus saw them as dirty. Eating pork meant crossing invisible social boundaries.

Weirdly, this even seeped into jokes, insults, and proverbs. You might hear people say, “Don’t act like a pig!”—implying someone’s behaving crudely. Go to rural north India today, and pork is more likely to show up on the plates of tribal communities or Dalits (now known as Scheduled Castes), but rarely in the homes of temple-going Brahmins or city folks on a satvik diet (one focused on purity and health).

Here’s another angle: ritual purity. Many Hindus believe food carries spiritual importance. Temple kitchens, for instance, have strict rules about what can be offered to deities or served as prasad. Pork never makes the list—and neither does beef. Even garlic and onions are avoided during fasts in some families for similar reasons. The philosophy? Keep it clean, light, and pure, both for spiritual and physical health.

This preference has another layer—Hindu festivals. Take Diwali, the biggest celebration, or Holi, the riotous festival of color. Feasts center around sweets, semolina halwa, and vegetarian curries. The rare households who do eat meat usually stick to chicken, lamb, or fish. Pork’s off the menu, sometimes more for tradition than any written rule.

As India urbanizes, some of these boundaries get blurrier. Pork is trendy among younger foodies, especially in Goa (famous for vindaloo) or the northeast, where tribes like the Nagas prize smoked pork. But if you ask the average Hindu household in Delhi or Chennai, their association with pork is—well, almost nonexistent.

Health, Hygiene, and Historical Realities

Hygiene isn’t just a modern concern; it was a central part of ancient Indian life. Without today’s refrigeration, raising pigs was risky. Pigs root around in filth; they eat absolutely anything, from tossed-out scraps to, well, things most people don’t want to think about. That made pork a tricky meat to eat safely in tropical climates, where parasites and diseases could thrive.

This wasn’t unique to India. In warmer parts of the Mediterranean and Middle East, pork disappeared from menus for similar hygiene reasons. Strict dietary codes evolved to protect people from food-borne illness. Many Jewish and Muslim dietary laws around pork, for instance, probably started partly for this reason—and in India, these attitudes rubbed off over time, too.

Here’s a jaw-dropping fact: India records fewer food-borne outbreaks of trichinosis (a pig-borne parasite) than countries where pork is a staple. While chicken and mutton sometimes cause food poisoning, pork’s near-absence from mainstream markets helps India dodge one type of health scare, even today.

| Meat | Annual Consumption per Person (kg) | Associated Foodborne Illness Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Pork | ~0.5 | Very low |

| Chicken | 3.2 | Medium |

| Mutton | 1.8 | Low |

This persistent caution stuck, even as global cuisines became popular in cities. Walk into a big Indian supermarket and pork occupies a tiny shelf, mostly imported sausages and bacon for a small, cosmopolitan clientele. By contrast, chicken is everywhere. Why risk eating something with a checkered reputation for safety when there are so many delicious, locally trusted options?

Of course, not everyone agrees with this view. Food historians sometimes argue that pork vanished more for religious politics than health. Still, the result is the same—compared to East Asia or the West, pork just doesn’t have a home in the mainstream Indian kitchen.

Regional and Modern Exceptions: Pork on Indian Plates

Let’s not paint all of India with one brush. Pork isn’t vanished; it just got regional. Step into Nagaland or Mizoram in the northeast, and pork curry simmers over every home stove. Tribal communities like the Bhils and Gonds in central India have their own traditions, where pork is served for festivals and rituals. Even in Goa, pork vindaloo (brought by Portuguese colonizers in the 16th century) is legendary, sizzling with vinegar, garlic, and spice.

Christians in Kerala and Mangalore use pork for everything from spicy sorpotel to sausages. In parts of Bengal, wild boar is still hunted (illegally, these days) for spiritual festivals. And if you’ve ever wondered what Anglo-Indian food is, it’s fusion cuisine packed with pork and beef, popular among families that descend from British-Indian marriages.

India’s immigrant and expat communities are changing the pork map, too. Chinese and Tibetan restaurants in Kolkata, Delhi, and Bangalore feature pork momos, chili pork, and sticky ribs that draw young, food-loving crowds. Food-delivery apps like Zomato show pork growing fast among the top-earning metros. Instagram foodies post about bacon tacos and pulled pork sliders at trendy cafes.

But numbers don’t lie. According to a 2022 survey by the National Family Health Survey, less than 5% of Hindus reported eating pork regularly, compared to over 70% who ate chicken or fish. It’s a curiosity, not a staple. When Hindus do explore pork now, it’s usually more about trying global flavors than keeping a forgotten tradition.

“Food taboos are about belonging: to a caste, a religion, or a modern tribe. To eat pork for many Hindus isn’t just about taste. It’s about what that act means.” — Dr. Krishnendu Ray, food historian at New York University

Here’s a tip if you’re traveling in India: never assume a menu will have pork unless you’re in Goa, the northeast, or a restaurant run by Christians or expats. If you have dietary restrictions, always double-check with your host. Chances are, you’ll find more paneer tikka than pork chops on offer.

What This Means for Today’s Indian Cuisine and Identity

The Hindu tradition of not eating pork does more than shape home kitchens—it ripples across the entire Indian dining scene. You’ll notice cookbooks rarely feature pork recipes. Major hotel chains don’t even serve pork at Hindu wedding banquets. Even street food, which in other parts of Asia often uses pork, leans heavily on chicken, eggs, or veggie options in India.

It also means that local butchers in most Hindu regions barely handle pork economically. Muslim and Jain businesses avoid it for their own reasons, and Hindu vendors usually prefer to stick to chicken or fish. The result? Pork costs more, is less fresh, and is often seen as a ‘niche’ product for a small audience.

This dietary boundary quietly shapes friendships, too. When Hindus and Muslims or Christians gather, menu planning gets creative. The focus turns to what unites, like smoky kababs, spicy paneer, or everyone’s childhood favorite: chaat. Pork is agreed to be skipped to keep things harmonious.

Some young Indians are chipping away at food taboos, but these shifts happen slowly. Cookbooks from the West glamorize bacon and pulled pork, but home chefs often substitute chicken or jackfruit. It’s a blend of curiosity and caution. Google Trends showed ‘pork recipes’ spiking in Indian metro cities during the pandemic lockdown, but street-side chaat or butter chicken recipes remain the long-term winners.

So why do Hindus not eat pork? History, health, caste, and habit, all tangled together. It’s partly about religious identity, partly about practical decisions, and always about the deep ties between food and belonging. For visitors or food lovers, the more Indian food you try, the clearer this becomes—not in loud bans, but in the quiet, everyday way menus and kitchens reflect centuries of belief and change.